Through personal stories and heartfelt reflections, she challenged the students to see the courage and sacrifice of our servicemen and women in a deeply personal way. Her speech transcript is published below:

Just three days ago, we celebrated our 110th Anzac Day. Regardless of whether that meant you attended a dawn service, watched the Anzac march, realised that Woolies wasn't open, or stood in a long line to get dinner at a pub, we gather here today to remember the sacrifice made by our armed forces. Anzac Day stretches far beyond history textbooks and old photographs. It serves as a reminder of the courage, sacrifice, and camaraderie of our soldiers. It’s a day to remember real people; young men and women, many our age; who stood up in the face of fear, not for fame or glory, but for the service of our nation.

Anzac Day marks the beginning of the assault on Gallipoli, signifying true heroism from the Australian and New Zealand armed forces. The assault was a fight put up in unexpectedly harsh conditions, serving as a testament to our soldier’s unwavering dedication, resilience and mateship. According to soldier recounts, this is what our forces experienced.

“At 4:00 a.m., April 25th, 1915, the first boats set out in the darkness, carrying anxious soldiers toward the Gallipoli Peninsula. It was a still night. There was hardly a breath of wind. Every sound seemed magnified tenfold and it seemed impossible that the noise of the boat hoists could escape being heard by the enemy a few miles away. We eagerly scanned the direction of the shore, the loom of which could just be seen, to see if we could detect any movement, but all was still.

By 5 a.m., the boats approach the shore and soldiers realise they are landing at the wrong location - they’re confronted by steep, rugged terrain instead of the expected flat beaches. Confusion spreads, but too much of a stir has been made to turn back. Orders are shouted over the calm sound of waves and the creak of oars. The first bullets pierce the air. Gunfire erupts from Turkish forces on cliffs above. Arriving soldiers leap into deep water under fire, some drowning under the weight of their packs.

6 a.m. ANZAC units are scattered, lost in the mountainous terrain. Soldiers claw their way up the steep slopes, many knocked back by falling rocks or other soldiers. The Turkish defenders, entrenched and relentless, rain down fire. Despite the carnage, the ANZACs press forward, driven by sheer determination and the bond of mateship.

As the sun continues to rise, light is cast on the horrors of the battlefield. Soldiers lay across the beach, wounded or killed. The ANZACs dig in, creating makeshift trenches to shield themselves. Swarms of flies infest the air. The sun scorches down onto the blood-stained sand.

By midday, Reinforcements arrive, but the situation remains dire. The heat is oppressive, and the men are dehydrated and exhausted. Supplies are scarce, and the wounded cry out for help. Amidst the despair, soldiers run amongst the gunfire, risking their lives to drag their wounded comrades to safety.”

Out of the 16,000 soldiers that sailed out to ANZAC Cove that day, 2,000 were wounded or lost their lives. For the remainder of the Gallipoli campaign, 12,000 ANZACs were killed in action or wounded before the evacuation in December of 1915.

The Gallipoli campaign continued until January of 1916. Over 8 months, the ANZACs advanced little further than the positions they had taken on that first day of the landings. The campaign instead became known for brutal fighting and heavy casualties for both sides. After Gallipoli, ANZACs established a reputation for bravery, resilience, and a unique sense of "ANZAC spirit". While the campaign was ultimately a military failure, the courage and enduring spirit displayed by the Australian and New Zealand soldiers resonated deeply, emphasizing our qualities of mateship, and a strong sense of national identity.

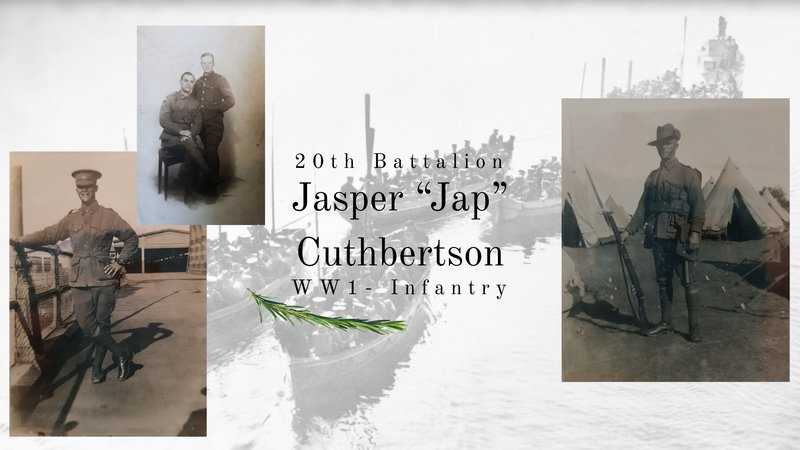

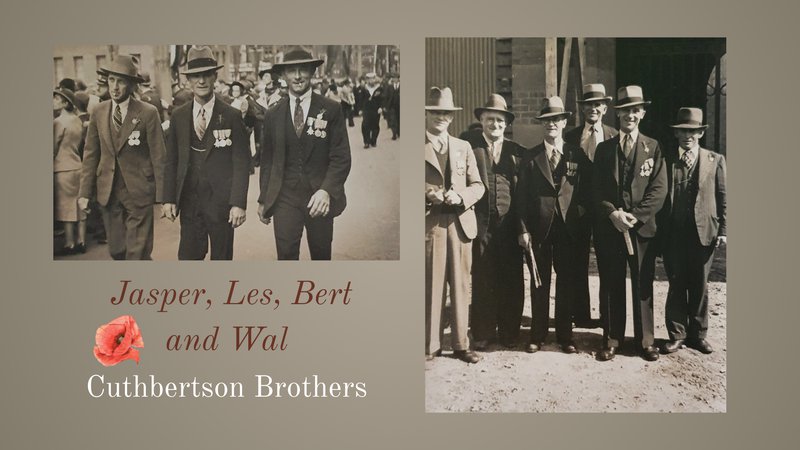

My great-great-grandfather, Jasper Cuthbertson, was one of four brothers who served in the Australian Army in WW1. After voluntarily enlisting, Jasper, Les, Bert, and Wal were sent to commence military training with the 20th infantry battalion. The 20th Battalion was amongst the troops that participated in the Gallipoli campaign. It was raised in Liverpool in early 1915, to form the fourth Battalion of the 5th Brigade in the 2nd Division, and its soldiers were drawn from NSW, like the rest of the 5th Brigade.

The 20th left Australia in late June 1915, trained in Egypt from late July until mid-August, and on 22 August landed at ANZAC Cove. Arriving at Gallipoli just as the August offensive petered out, the 20th's role there was purely defensive. Although I never got the chance to meet Jasper, I got to hear a bit about his war experience. He firmly believed that more men died of the harsh conditions and widespread disease than from the Gallipoli campaign conflict itself. Throughout his service, Jasper would often write and hear from home.

This somehow escalated and led to Jasper’s own brother, Les, trying to kill him. Clearly someone was jealous of the number of letters he received while on service. “Remember those goods days Dot, little did we think then that in the near future, some of the same lads would be playing in such a bloody game as this, where there is no referee to stop a man from playing dirty, where there is no half time called, unless it is hospital or pushing up daisies.” While researching his military history in the national archives, I was quite surprised to see more records of deducted pay than records of his service.

He didn’t seem to like going back to work, and he was often punished for his late returns from his leave entitlements. After surviving and being evacuated from Gallipoli in December of 1915, Jasper was then posted to France to fight in the battle of Pozieres, where he spent more time in his so-called unofficial holidays to British hospitals than where he was meant to be posted. He and all three of his brothers returned safely to Australia in 1919, with minor injuries sustained.

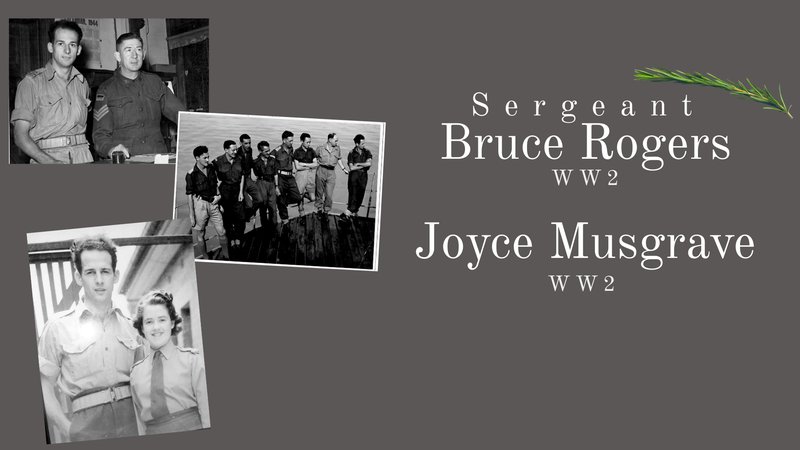

My great-grandfather, Bruce Rogers, served in the army throughout WW2. He voluntarily enlisted on the 19th of June, 1940 into the ambulance section of the Australian armed forces, though he had his heart set on becoming a fighter pilot. Working as a photographer before enlisting, he invested all of his savings in learning to fly tiger-moths at Newcastle aero-club. His medical corps training commenced in Townsville in 1940, before he was transferred to become a war photographer.

He served mostly in the pacific theatre, and witnessed some of the most brutal fighting experiences Australian soldiers have had to face. In the early few years of the war, Bruce wrote to Joyce Musgrave, a woman who ended up becoming my great-grandmother. A few months into their relationship, whilst out in the city, Joyce’s friends dared her to enlist after hearing about her relationship with a soldier. Not even an hour later, she signed the attestation form you see on the screen. She was posted across Australia as an instrument operator and administration worker until the end of World War 2.

The photos you see on the next few slides are photos he captured of his war experience throughout the pacific conflict and postings in the middle east during his postings to a number of battalions in numerous conflicts. He witnessed the surrender of numerous Japanese forces, and helped targeted communities when serving in Africa. I unfortunately never had the opportunity to meet Bruce or Joyce. Bruce shared little about his war experience, but he experienced and photographed across the pacific and Africa. Today, I have the privilege to wear his five badges, signifying his service and dedication to our nation.

Bruce and Joyce were discharged after the conclusion of World War 2, with no injuries.

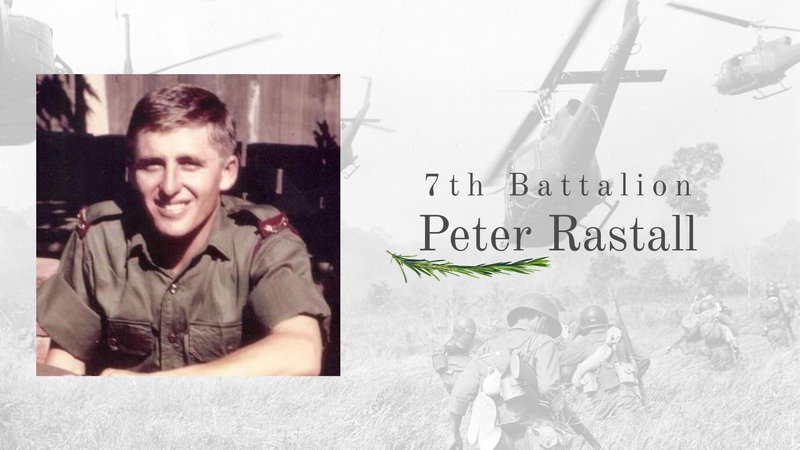

Peter Rastall, my great-uncle, served in the Vietnam War throughout 1970 in the 7th battalion. In late 1969, he was conscripted by being pulled from the birthday lottery, and commenced training for his deployment against the Vietcong in early 1970. As a forward-scout, Peter had the role of being the first in his platoon to traverse the trap-ridden jungles of Vietnam. His battalion regularly carried out ambush attacks, with extensive patrolling, intel gathering and in-force reconnaissance practices. Peter was discharged at the end of 1970 medically. Although Peter returned to Australia safely from Vietnam, he passed away in 2012 of leukemia as a result of exposure to agent orange. His children were also greatly affected by the harmful effects of the chemical. Peter was sympathetic for all affected, especially those he fought against throughout the war.

Each of these are only chapters of the story of our ANZACs. IJust three days ago, we celebrated our 110th ANZAC Day. Regardless of whether that meant you attended a dawn service, watched the ANZAC march, realised that Woolies wasn't open, or stood in a long line to get dinner at a pub, we gather here today to remember the sacrifice made by our armed forces. ANZAC Day stretches far beyond history textbooks and old photographs. It serves as a reminder of the courage, sacrifice, and camaraderie of our soldiers. It’s a day to remember real people; young men and women, many our age; who stood up in the face of fear, not for fame or glory, but for the service of our nation.

Lest we forget.